[Long live the whores / Hooray for hookers] Note on the exhibition’s guestbook

[Long live the whores / Hooray for hookers] Note on the exhibition’s guestbook

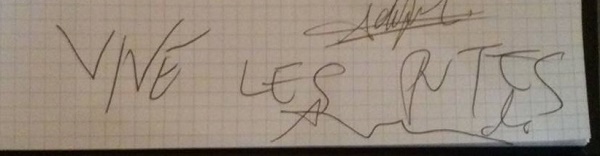

Marianne Breslauer, Die Fotografin, 1933, Winterthur

The second part of the exhibition “Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?” is in view at the Musée d’Orsay (until January 24, 2016), and covers the 1919-1945 period. Compared to the first part of the exhibition at the Orangerie, the tone changes, of course. First of all because this is familiar territory or so for anyone with a modicum of curiosity: most names are well known, most artworks are contextualized with familiar references. All right. But this all begs the question of what is this “modicum of curiosity?” How can one nurture it? Not really with history books (see the end of the previous post), but, in my case –I realize this with modesty and gratitude–, it was largely sustained by the series of exhibitions programmed these past few years by Marta Gili, the director of the Jeu de Paume (the only women currently running a prominent Parisian museum since Mme Baldessari was let go). Sure, I knew of Germaine Krull, Florence Henri, Laure Albin Guillot, Berenice Abbott, Claude Cahun, Lisette Model, Lee Miller (see also), and even of Eva Besnyö (but not of Kati Horna), but I was not really acquainted with their work for the majority of them. Continue reading

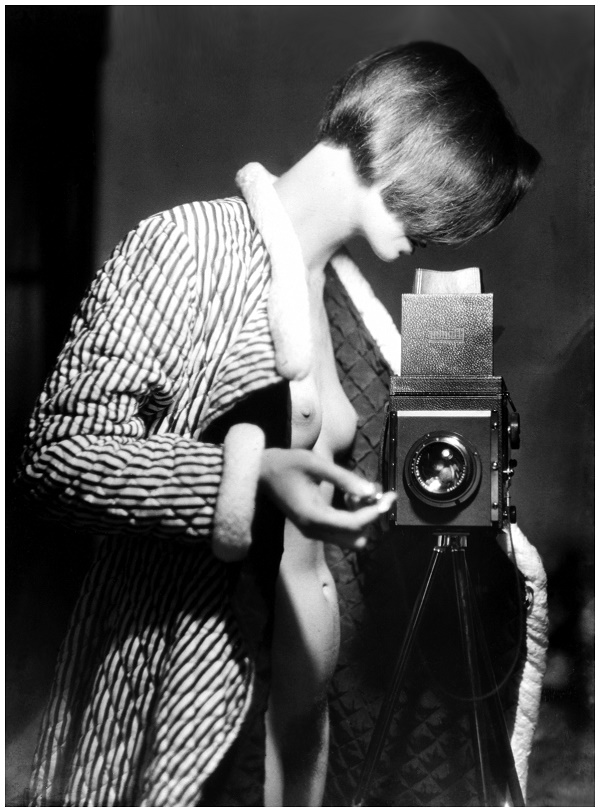

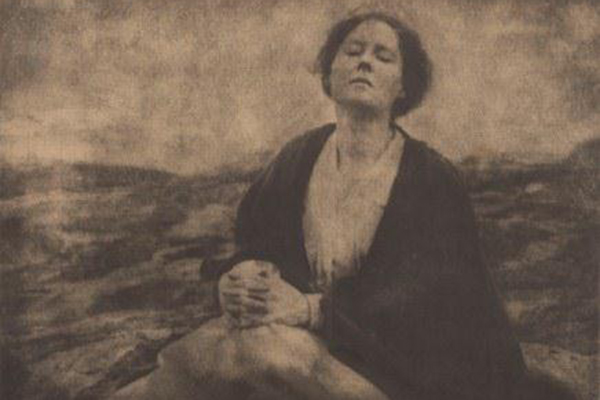

Gertrude Käsebier, The Heritage of Motherhood, 1904, NY, MoMA

On the threshold of the first part (1839-1919) of the great exhibition on women photographers (through January 24, 2016), I wondered how many women photographers I could name in that timeframe. I am not an expert on the nineteenth century, but I am not an ignoramus either, and I think I can list fifty male photographers from this era without too much trouble. Try it out for yourself. I ended up naming only two women: Julia Margaret Cameron and Anna Atkins (who, incidentally, was more precisely a botanist using photogenic drawing, but anyway…). Once inside the exhibition, I recognized two names which were familiar but did not automatically came to mind, Gertrude Käsebier (who took the splendid Mater Dolorosa pictured above, and a portrait of Sioux activist Zitkala-Sa pictured below) and Lady Hawarden. Well, this is quite clear and quite telling: a total of 2 or 4 out of the 90 artists featured here, not even 5% at best. Among all the artistic disciplines of the nineteenth century, photography might be the one (along with military music, perhaps?) in which women have been erased the most, a fact that this first half of the exhibition (at the Orangerie) allows us to realize, invaluably so. That is to say, it enables us to discover these women photographers and their talents and, at same time, to uncover how, if not why, they have been occulted thusly from the history of photography, then as well as now. Continue reading