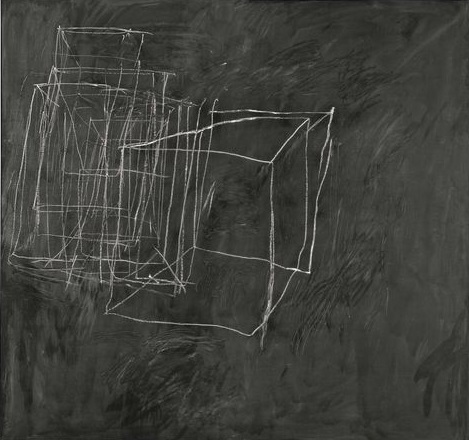

Cy Twombly, Night Watch, 1966, industrial paint, wax pencil on canvas, 190x200cm

I must admit from the get-go that I have never been a die-hard fan of Cy Twombly’s work; I do like his photographs and their faded hues, but his paintings often left me skeptical, or even worried. His retrospective at the Centre Pompidou (November 30, 2016 – April 24, 2017) had the merit to help me understand why. To me, Twombly oscillates between two poles: one is austere, abstraction-oriented, pared down, reduced to its simplest expression; the other is expressive, exuberant, almost baroque, and weighed down with references that can be seen as pretentious.

Cy Twombly, Nine Discourses on Commodus, 1964, on view at the Guggenheim Bilbao

Among the works I include in the latter trend, the worst is probably the series Nine Discourses on Commodus, painted in reaction to JFK’s assassination, dixit Twombly. On a grey background, some cockscomb-like yellow, pink and red outbursts make for nine canvases aligned without grace or purity —the Emperor’s psychology translated in impulsions of color. To me, the constant anchoring to Antiquity, the pseudo-historicity, the titles ceaselessly referencing Virgil, Homer, Troy (to use “Iliam” instead of “Ilium” because the “A” embodies virility is nothing but pedantic), Sesostris and Ra, Achilles and Patroclus, somewhat jumbled together, reveal Twombly’s “model student” dimension, as a cultured American wed to an aristocrat from Rome, impressing his puritan provincial fellow countrymen with Mediterranean culture and sensuality (which don’t ring true, in my eyes). This naïve thirst for grandiosity leaves me indifferent.

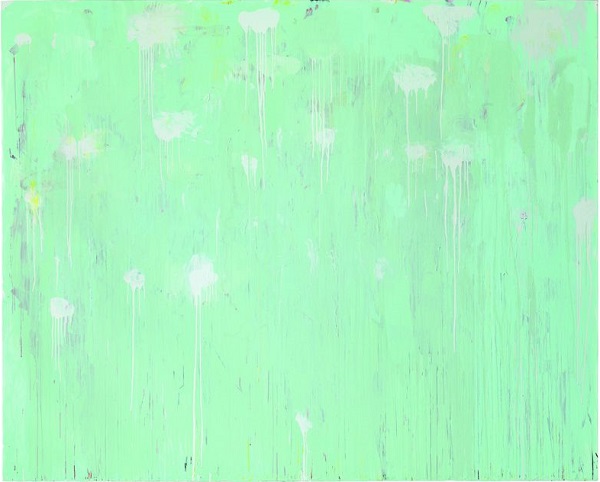

Cy Twombly, Untitled (A Gathering of Time), 2003, acrylic on canvas, 215,9×267,3cm, coll. Brandhorst

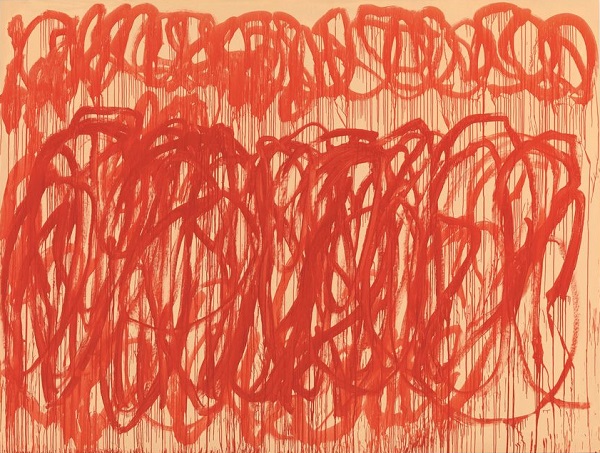

On the contrary, Cy Twombly’s first paintings, austere scratches, or his return after 1964 to black and grey backgrounds on which white wax traces sketches and diagrams (pictured first), or his series A Gathering of Time, precious white bombs exploding on ethereal backgrounds, are all wonderful in their purity and pared down simplicity, stripped of the whole neoclassic expressionist pathos of his other works. (Despite its title, I would add to these the first series of large red and white Bacchus (pictured last).) However, as he remarked after Commodus, these artworks were created in response to the lack of critical and commercial success of his previous paintings. Where to place the —fluctuating— truth of Twombly’s construction/destruction of painting?

Cy Twombly, Winter’s Passage Luxor (Porto Ercole), 1985, wood, nails, paint, color pencil on paper, 53,5x105x51cm, Kunsthaus Zurich

There are some very beautiful little sculptures, assemblages of objects coated in white paint and plaster. The title and aspect of the sculpture pictured above evoke ancient Egyptian funerary boats, going from the right bank of the Nile, symbolizing life, to the left bank, the mortuary one (Caravaggio died at Porto Ercole, another reference…). And some superb photographs: as early as 1951, at the Black Mountain College, he creates still lifes of glasses and bottles echoing Morandi; in 1953, an abstract, minimal interplay picturing a table and its tablecloth; later, a few sensual Polaroids in pastel colors, discrete short poems, like these lemons from Gaeta. When he lets go in this way, without showing off his culture or calculating his effects, Twombly is at is best, in my eyes.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Bacchus), 2005, acrylic on canvas, 317,5×417,8cm, coll. Brandhorst

I’m rereading Roland Barthes, from whom Yvon Lambert had commissioned two essays on Twombly: a reluctant Barthes who cannot bring himself to name the painter in one of the two texts, and writes about “TW” —a rather transparent distancing move. The written dimension of TW’s canvases and their Greco-Latin references resonate with Barthes. For the scholar, it is an opportunity to write beyond Twombly, not so much about the painter but rather about gestures, scratching, smearing, and, precisely, writing. (Also: about aesthetics, which should be a “typology of discourses,” focusing not on the artwork, but its perception, “as the spectator makes it talk in him/herself.”) Barthes deciphers the painter’s approach which consists in “holding in front of humans that which they crave for: the bait of meaning,” thanks to the titles of the paintings, themselves images for which “the reference matters, and the contents do not.” The art of Twombly, Barthes writes, lies in having “imposed the Mediterranean effect from a material that has no analogical relation to the great Mediterranean radiance.” Later on, he writes that culture, for the painter, is “an ease, a memory, a posture, a gesture of Dandyism.” The art of criticizing with elegance…

Read this article:

in the original French, alt.

in Spanish

Original publication date by Lunettes rouges: February 11, 2017.

Translation by Lucas Faugère

Pingback: Le mythe Twombly | lunettesrouges1