Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017

Museums, as objects, are here to tell us about an elsewhere that we don’t know, in order to educate us and provide us with rational, learned, Cartesian discourses —especially ethnographic, archeological and natural history museums. Of course, this is set in a model that structures our society and outlook. The same artifacts won’t relay the same discourse whether they are displayed in a “cabinet of curiosities,” a colonial museum, an antiques shop, a flea market or the Quai Branly museum. Our ideology in showing and exhibiting imposes itself on the artifact and our gaze has to conform to it. Sure, we can choose to be docile, because we are respectful, conformist, and learning; or we can choose to be skeptical and reluctant when faced with, for example, the national narrative of Napoleon III’s Second Empire, the racialist phrenology of colonial exhibitions, or falsified colonizing archeology in Moshe Dayan’s style. However, we always remain within this rational logic, consuming meaning and context.

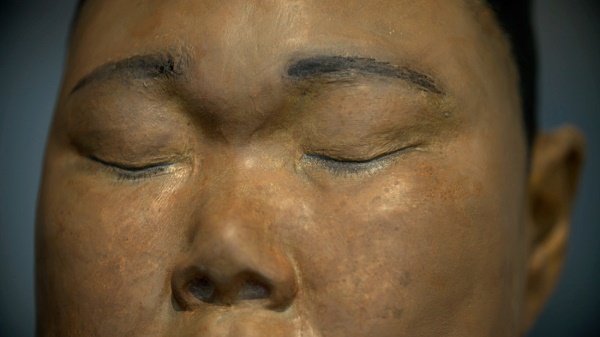

Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017 (phrenological bust, XIXth-century plaster molding of an indigenous person, Musée de l’Homme)

It is always so —except when we sleep. A sleep that is not the deep sleep, too remote from reality, but the light sleep, the somniculus, which gives its title to Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s exhibition. Somniculus is currently on show at the Jeu de Paume in Paris (in its Satellite programme, February 14 – May 28, 2017) and at the CAPC in Bordeaux (February 2nd – April 30, 2017); then at the Maison d’art Bernard Anthonioz in Nogent-sur-Marne (November 30, 2017 – February 4, 2018). The exhibition is the first installment in the series “The Economy of Living Things” by Ghanaian curator Osei Bonsu, focused on the mobility of bodies and objects, the archeology of time, and history as the repository of living memory.

Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017

So what exactly is this light sleep, this state of soft levitation, reduced availability, altered consciousness (words drawn from the artist’s statement in the catalogue)? It is a moment of pause, distraction and sleep of reason (though without nightmares or monsters), a moment for us to let go —instead of admiring or analyzing—, feel emotions and relate to the objects, our imagination running past the visible. The approach Ali Cherri favors is more animistic than rational, allowing the objects to become doubles, protectors, and autonomous, floating forms that engage us differently and therefore propel us in yet another fiction. In relation to the catalogue’s epigraph taken from John Berger (without crediting him, sadly), it is an experience of a-temporality (such as ecstasies, orgasms or near-death experiences), during which “the imagination of living beings covers the totality of the field of experience and exceeds the outlines of individual life or death, [neighboring] the languishing imagination of the dead.”

Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017 (Louvre Museum)

Ali Cherri films empty rooms in museums —at the Quai Branly Museum, the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, the National Museum of Natural History, the Louvre and the Musée de l’Homme. There, sometimes lit only by torchlights, appear sarcophagus, wax anatomies, stuffed animals, busts of natives molded in plaster, écorché figures, skeletons, masks, votive statuettes, mummified birds… about which we won’t know more, as they are all torn from their history, context and culture. Many have their eyes shut —they are sleepers too, waiting to be woken up, assuredly. Sometimes, a man, the artist, sleeps on a bench in a museum room, or in his white bed. Like him, deprived of context or discourse, we won’t know anything about these objects, and we are barely able to identify, thanks to vague memories of distant classes, this Egyptian period and that Pre-Colombian culture, without being too sure of it in fact.

Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017 (phrenological bust, XIXth-century plaster molding of an indigenous person, Musée de l’Homme)

This distance with culture, this form of hypnosis, this numbing of reason leave space to, rather than a formalist ahistorical reading, a magical, animistic relationship with the objects, whose point of view we could, in this light sleep, embrace, or whose psyche we could absorb, achieving harmony or symbiosis with them. It is a strange and difficult experience Ali Cherri invites us to. I remember one similar experience at São Paulo’s art museum, where the main room has some boldness to it and where, quite simply, the labels are behind the artworks rather than beside them —for the cultural areas in which I am knowledgeable, the situation calls for a kind of erudite quiz: is this dark Saint Anthony a piece by Zurbaran or Murillo? This helps to avoid preconceptions and allows for looking at the artwork as such, without being too preoccupied with its historical and stylistic context at first. That being said, I encountered two barely decorated terracotta vases near the entrance, and knowing nothing about them, I tried to place the culture they come from, maybe Macedonian, maybe Mycenian… and finding myself unable to do so, I think —now, in retrospect— that I probably let myself go in Ali Cherri’s light sleep and felt content to just take in, for a good while, such perfect shapes and pure designs. It is only afterwards that I went behind the vases to read the label: Pre-Colombian funeral urns. Maybe it is easier to give way to the somniculus when death is present.

Photos courtesy of Jeu de Paume

Read this article:

in the original French, alt.

in Spanish

Original publication date by Lunettes rouges: February 22, 2017.

Translation by Lucas Faugère

Pingback: S’endormir au musée ? (Ali Cherri au Jeu de Paume) | lunettesrouges1