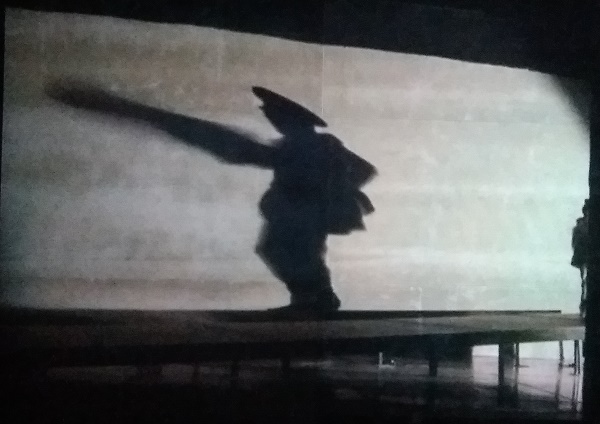

Ali Cherri, Somniculus, 2017

Museums, as objects, are here to tell us about an elsewhere that we don’t know, in order to educate us and provide us with rational, learned, Cartesian discourses —especially ethnographic, archeological and natural history museums. Of course, this is set in a model that structures our society and outlook. The same artifacts won’t relay the same discourse whether they are displayed in a “cabinet of curiosities,” a colonial museum, an antiques shop, a flea market or the Quai Branly museum. Our ideology in showing and exhibiting imposes itself on the artifact and our gaze has to conform to it. Sure, we can choose to be docile, because we are respectful, conformist, and learning; or we can choose to be skeptical and reluctant when faced with, for example, the national narrative of Napoleon III’s Second Empire, the racialist phrenology of colonial exhibitions, or falsified colonizing archeology in Moshe Dayan’s style. However, we always remain within this rational logic, consuming meaning and context.