Anton Giulio Bragaglia and Arturo Bragaglia, Salutando, 1911, 17.5x23cm, Galleria civica in Modeno

To question the nature of photography is the aim of Pandora’s Box, an exhibition curated by Jan Dibbets at the MAMVP in Paris (a museum the artist is familiar with), from March 25 to July 17, 2016. Hailing from conceptual art, Dibbets was among the first to examine photography itself (alongside William Anastasi, then Michael Snow, John Hilliard, Tim Rautert and Ugo Mulas). Around 1970, he created a series of photographs addressing the processes and mechanisms of photography , as well as its essence, as opposed to the images represented: the “how” of photography rather than its “what.” In this exhibition, Dibbets presses forward with these same concerns, reframing them within the history of photography, and nourishing them with readings of Vilém Flusser’s ideas –a thinker he discovered while preparing the exhibition. (This fact was of great interest to me, of course; it is more thoroughly explained in a video of his interview with Fabrice Hergott than in the catalogue).

Pandora’s Box has been put together by an artist, not an art historian, and therefore there were some liberties taken, some partial choices made, some incongruous selections (especially in the last section, which was quite disappointing), and some bizarre omissions (from the five precursors I just cited, only Anastasi and Snow are featured, and Mulas’ absence in particular is baffling, if it is not simply a petty move by Dibbets). Those choices will appeal or not to the visitor, but –at least until the last section– they make for a compelling exhibition.

Désiré-François Millet, Paintings in Ingres’ studio, circa 1851, daguerreotype, 17.2×21.2cm, photo Guy Roumagnac, Musée Ingres, Montauban, France

Pandora’s Box is firmly rooted in the history of photography: one of the first artworks is Désiré-François Millet’s photograph of a painting by Ingres that is now lost (with the famous Madame Moitessier in the background) –the painting was probably destroyed by Ingres’ second wife, Delphine Ramel, because the canvas, hung above the marital bed, represented the painter’s first wife, the naked and voluptuous Madeleine Chapelle (who might have been a “substitute”, but this is another story). The fact that this painting has been saved from oblivion by photography was and still is an amusing turn of events, considering how vocal Ingres was about his dislike for the new medium (the painter signed a petition “against any consideration of photography as art”). By the way, this reproduction of a daguerreotype is currently on view at the Petit Palais, and this clues us in to this exhibition’s lack of consideration for vintage or original prints: what is important here is the image, duplicated, countertypeed, multiplied –not the original and its materiality (except, it would seem, in the last room…).

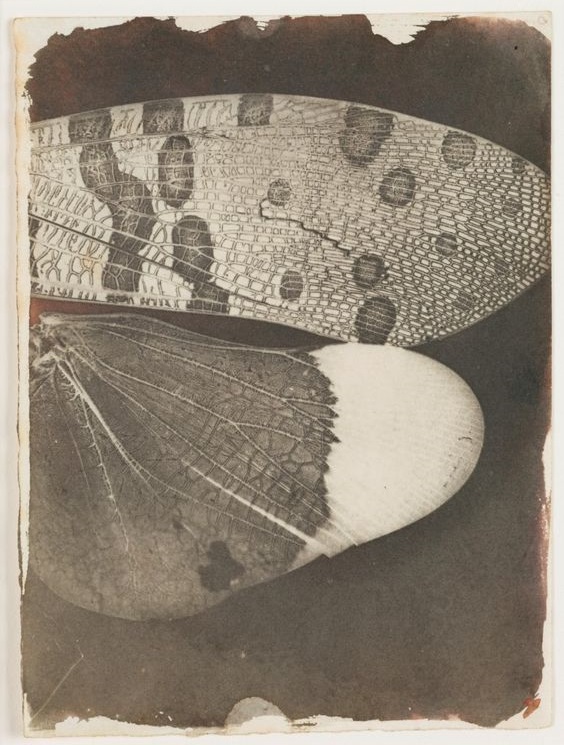

William Henry Fox Talbot, Photomicrograph of insect wings, circa 1840, 32x21cm, Lacock Abbey

Going forward, we encounter (reproductions, for the most part, of) historic landmarks of photography, from Nicéphore Niépce to Hippolyte Bayard, arranged to support a reflection on fragility, reproducibility, and disappearance (such as in Niépce’s physautotype, La Table servie and its reconstitution). This second section focuses on photographs as imprints, as traces of things (and therefore photograms are featured prominently), be they plants, shells, laces, dragonfly wings, or the sky, the stars, the moon… following the steps of the pioneers who succeeded in representing the skies and even infinity.

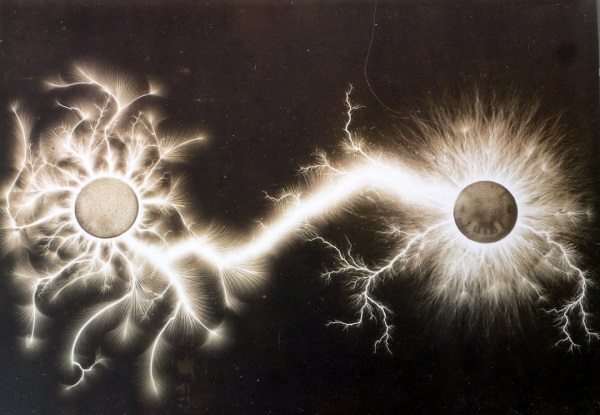

Etienne-Léopold Trouvelot, Direct Sparks obtained with Ruhmkorff’s induction coil or Wimshurst’s influence machine, aka Trouvelot figures, 1888, aristotype, 40x60cm, CNAM

All of this ushers the photographic discovery of what the human eye cannot perceive: what is infinitely far and what is infinitely small, what X-rays reveal (the exhibition poster features a skull by Meret Oppenheim), or such fleeting phenomena as Trouvelot’s sparks (also a rather ill-advised amateur entomologist [pdf]).

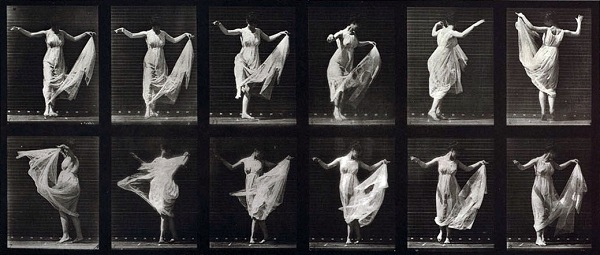

Eadweard Muybridge, Plate 187, Dancing Fancy, n°12, Miss Larrigan

These images are then followed, quite logically, by the photography of movement, represented in a splendid room devoted to Muybridge (accompanied by only four photographs by Marey, regrettably: spectacle often trumps science in this exhibition). Jan Dibbets tritely emphasizes their contribution to film; I personally see such chronophotographs as “anti-cinema”, as movement deconstructed to produce still images rather than still images animated to achieve movement. Besides the well-known studies of naked walkers, I enjoyed the subtler eroticism of the veiled dancer pictured above, twirling around without actually revealing her charms. The Bragaglia brothers were also quite innovative (pictured at the top of this article), trying with their “photodynamism” to convey the feeling of movement rather than simply representing it. As for movement caught and fixed, look no further than Harold Edgerton’s famous drop of milk.

Gustave Le Gray, Marine, study of clouds, 1856-57, print on albumen-processed paper, from two negatives on collodion glass plates, 31×39.8cm, MUCEM, loan to the Musée de Troyes

A captivating step of this reflection on photography is embodied by Gustave Le Gray’s illustrious montage, for which the photographer paired together two images taken separately, one of the sky and one of the sea. Le Gray’s montage is a seminal source for all the debates on retouching and on photographic veracity, as well as the first example of an attempt to break off from realist, representational, indexical photography (was the montage explicit or covert?). That is to say: an attempt to create original work and therefore to represent –or even demonstrate– more efficiently, using a technology that is not equivalent (anymore) to the eye, that has become more than just a visual organ enabling identical reduplication, towards a creative dispositif. The next step is Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents: a series of pictures of clouds in which the shapes and figures take precedence over representation.

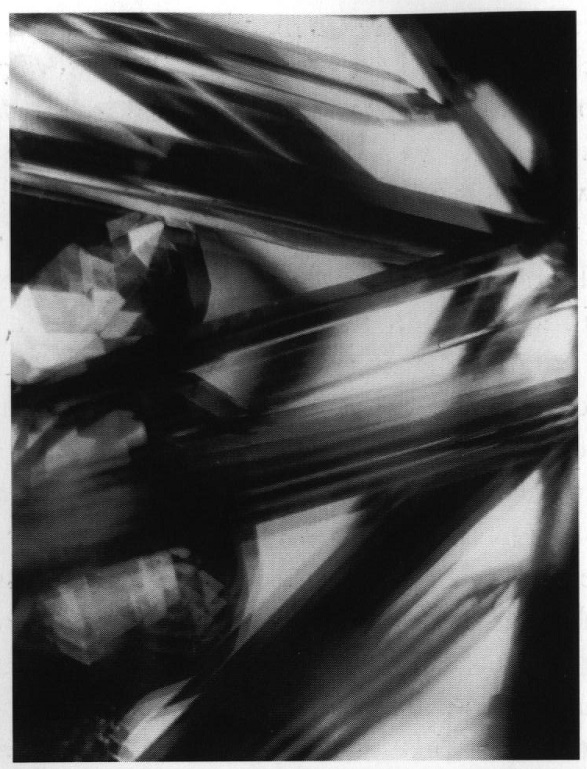

Alvin Langdon Coburn, Vortograph, 1917, 20.8×15.7cm, Eastman Museum Rochester

The move towards abstraction comes next, with photographs in which geometrical patterns cannot be identified as things –even if some claim that they are not truly abstract photographs but photographs of the abstract since they still capture reality, seen through a lens. Brassaï’s cobblestones and Paul Strand’s woods remain close to reality, whereas Alvin Langdon Coburn’s vortographic prisms veer off from it. This could have been the final room, with photograms by Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy, with several series by Bernd & Hilla Becher, Christian Boltanski or Hans-Peter Feldmann, with conceptual photographs by Anastasi, Snow and Dibbets (who is presenting only one of his photographs, tactfully).

The final images could then have been the sober, compelling artworks of James Welling or Liz Deschenes (two examples of contemporary experimental American photography), alongside final words by Flusser and Moholy-Nagy advocating the upending of rules and guidelines. The visitor would then have had nothing but praise for this photographic exploration, substantial both visually and conceptually.

Seth Price, Letters, 2012, fabric with printed lining, 243x243x5cm

It is a real shame then that the last section is actually a grouping of “photographic objects” –a loosely defined concept coined by the critic Markus Kramer–, that is to say picture-perfect photographs of tridimensional objects. Despite postmodern jargon on offer for explanation, the objects in the room don’t have much to offer beyond their spectacular nature.

Read this article:

in the original French; alt.

in Spanish

Original publication date by Lunettes rouges: June 3, 2016.

Translated by Lucas Faugère

Pingback: Revisiter l’histoire de la photographie (1. Dibbets) | lunettesrouges1

Pingback: Revisiting the History of Photography (2 – Élysée) | red glasses