Ugo Mulas, Autoritratto con Nini [Self-portrait with Nini], 1970, Verifica n°13 [not featured at the HCB Foundation]

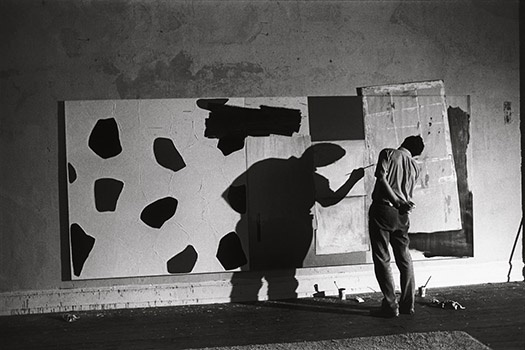

In front of artists, Ugo Mulas’ photographic work primarily depicts them at work, or alongside their artworks, sometimes quite plainly –for instance: a top-down view of Kenneth Noland (in black&white in the exhibition)– but most of time with an added twist, a personal outlook –a play on shadows (Jasper Johns, pictured above), on duplication (Roy Lichtenstein), or on the canvas used as a screen (Barnett Newman). Thus, in the face of the mysterious act of creation, the photographer’s capacity for critique shines through, as he goes beyond the mere documentary reportage, aiming to reveal a point of view, a critical narrative. This is especially obvious in his pictures of Lucio Fontana at work or, more precisely, of Fontana pretending to work, as the painter mimes his gestures to create an imaginary. As I wrote in the case of Fontana’s exhibition at the MAMVP in 2014, I personally think that it illustrates his awareness of photography’s inability to fully account for ineffable artistic creation, and therefore the need to stage the scene in order to truly show.

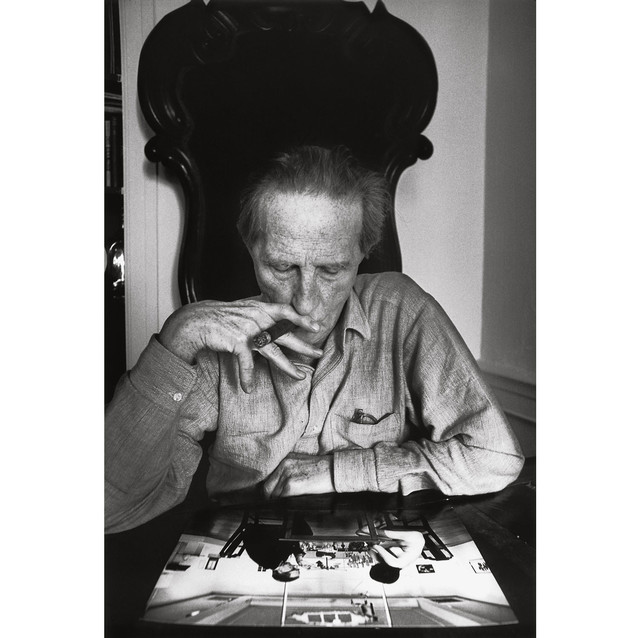

Ugo Mulas, Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1965

In some instances, the friendship and empathy between Mulas and his subject can be seen easily (in the case of Alexander Calder, for instance). However, I find more interesting the photographs in which the artist tries to elude the camera: those of Andy Warhol, too slick, too evasive to really let himself be captured; the seven extraordinary images of Marcel Duchamp who, at the time, was not creating artworks anymore, officially –all the while concealing his ongoing work on Étants Donnés. What is there to be done, then, with such elusive artists, artists who refuse to create? Their portraits? Sure. Mulas is indeed a great portraitist: see the radiant Alberto Giacometti modestly hiding his joy at the news that he has won the Grand Prize of the Venice Biennale; see the evil shade adorning Max Ernst’s brow aboard a vaporetto. Yet, with the ever-elusive Duchamp, Mulas had to step up his game, and find something beyond the portrait featuring the artist’s sly and enigmatic smile, or the pose next to an older artwork. Was it or Marcel or Ugo who thought of this image (pictured above)? Duchamp is sat, sucking on his phallic cigar, focused, leaning on the table before him (in another picture, he looks at the camera, but I prefer this one). He does not play chess, distancing himself from the action, once again: he plays with a photograph by Julian Wasser depicting him playing chess two years earlier with the young Eve Babitz, in the nude, in front of elements from Le Grand Verre. This fake mise en abyme is remarkably inspired, and very Duchampian I might add.

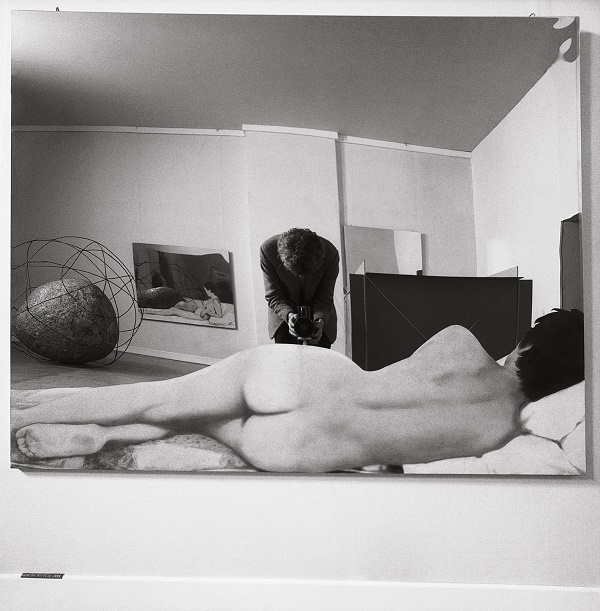

Ugo Mulas, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s room in the exhibition “Vitalità del negativo,” Rome, 1970

Among the photographs depicting artworks rather than artists, my favorite is the one in which the discreet photographer has to appear, not resorting to tricks that would conceal his reflection as he captures one of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s mirror-paintings. Ugo Mulas appears in this actual visual trap, his head bowed over his camera, himself becoming a double, as it is impossible not to see him above this naked woman seen from behind. Moreover, this produces an irresistible illusion, in which we imagine him facing the woman and photographing the genitals and breasts we cannot see.

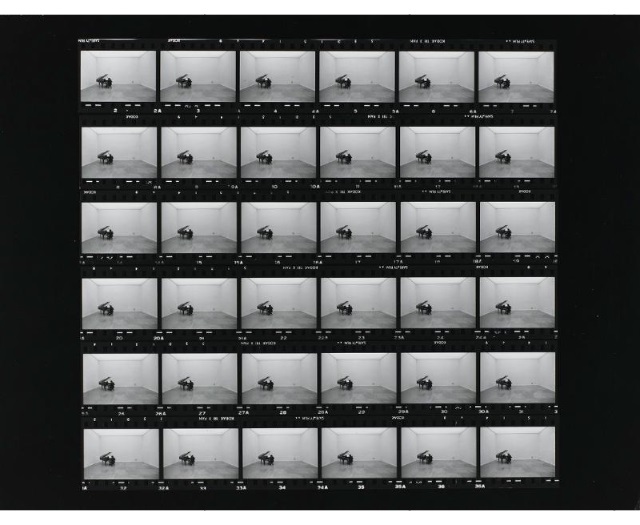

Ugo Mulas, Il tempo fotografico [Photographic Time], A J. Kounellis, 1969, contact sheet (Verifica n°3)

Other facets of Ugo Mulas’ œuvre remain to be shown in France, such as his work on fashion, jewellery, daily life in Milan at the onstart of the 1950s, the Campo Urbano events, or scenography. Another time…

All images © Estate Ugo Mulas, Milan – Courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples and Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation.

Read this article:

in the original French; alt.

Original publication date by Lunettes Rouges: January 26, 2016.

Translation by Lucas Faugère

Pingback: Ugo Mulas ou la vérification de l’art | lunettesrouges1

Pingback: Revealing Creative Genius(es)? Of Photography’s Imposture | artredglasses

Pingback: Revisiting the History of Photography (1. Jan Dibbets) | red glasses