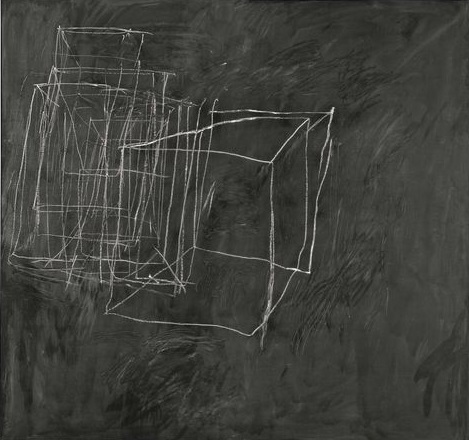

First, astonishment seizes you: what? a Bernard Buffet exhibition (at the MAMVP, October 14, 2016 – March 5, 2017)? Then, doubt unfurls: maybe I’ve let something slip by me? Am I missing out on some revelation because of my prejudices?

After having seen the exhibition, it’s nothing but consternation: how could they dare to make such an unconvincing show? Or is it that rehabilitating Buffet amounted to an impossible task? And if so, why put together this exhibition? To please Pierre Bergé, the ex-boyfriend, who owns a fair amount of the paintings on display (his portrait pictured last)? I cannot think so. This is not a rediscovery or rehabilitation, this is a “rebranding” —on the walls of the exhibition, a quote from Bergé: “[Buffet’s] prickly signature has become a brand name.” Is this actually the context in which we should apprehend this promotional relaunch?